The Online Peacemakers of Israel and Palestine

The true, unlikely story of coexistence on Clubhouse amidst a bloody war

Quick preface: I wrote this essay almost two years ago, in May 2021, during the latest battle between Israel and Hamas in Gaza and Southern Israel. I tried to get it published during the war itself, but sadly no major media publication wanted to run it. Perhaps stories like these do not fit the tidy narrative of media organizations, or pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian groups for that matter, who all make a profit peddling stories of conflict. Sadly, the old adage “If it bleeds, it leads” still rings true, particularly in this part of the world. Stories that portray the conflict in a different light do not typically get distributed widely. In this way, the media plays a role in perpetuating this conflict. The truth, as you’ll read in this story, is full of nuance and, sometimes, surprises. So today, in honor of Israel’s 75th birthday, and in commemoration of the Nakba, I am releasing this essay to the public, for free.

“These men are at peace with us; let them dwell in the land and trade in it, for behold, the land is large enough for them.”

-Genesis 34:21

“If you want peace now, you need to start working on it 20 years ago.”

-Reverend Dr. Gary Mason

For 75 years now, Israelis and Palestinians have been battling one another. We have been taught they are fighting over territory. I lived in, and reported from this land for a decade, and here’s a fundamental truth that I learned: They are fighting over something much more important than territory. They are fighting over a story.

Despite sharing a small parcel of land roughly the size of New Jersey, Israelis and Palestinians rarely get to hear each other’s stories. This wasn’t always the case. My Israeli-Jewish relatives wax nostalgic about the 1970s when they would drive into Gaza from the northern suburbs of Tel Aviv for the day to have lunch and go shopping. In today’s political context, this seems unimaginable. A physical barrier blocks Israelis and Palestinians from meeting each other in person in the West Bank. An airtight border prevents Gazans and Israelis from meeting. Nowadays, ordinary Israelis and Palestinians live their lives completely isolated from one another.

But on May 17th, 2021, at 5:08 pm PST, 4 days after Israel and Hamas began firing rockets and bombs at each other (again), a kind of “miracle” happened in the Holy Land, witnessed by half a million people around the world.

A large group of Israelis and Palestinians spoke to one another.

Yes, you read that correctly.

Hundreds of thousands of Israelis, Palestinians, as well as Jews and Palestinians in the Diaspora, listened to each other’s voices and stories, many for the first time. Like long lost lovers who have been kept apart, the conversation did not want to end. It lasted for 348 hours, or 14 and a half days, straight, 5 days longer than the war itself. More than 500,000 people in total listened to each other’s narratives

This online meeting did not make the headlines of any major newspaper at the time, even though it may be the largest collective dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians in history.

The so-called “miracle room” was possible thanks to the social media application, Clubhouse, designed for deep listening, and a group of moderators, or “mods” that learned on the fly how to foster genuine understanding by focusing on personal narratives

"Israelis and Palestinians have so much in common, but also so many differences. We can barely agree on terminology, and that's what makes this room such a miracle,” said Majed Oathman, 32, the Palestinian founder of the room who grew up in East Jerusalem and whose family lives in the Arab-Israeli village of Abu Gosh, known for Israeli-Palestinian coexistence and hummus everyone can agree is delicious.

Peaceful coexistence on social media between Israelis and Palestinians, particularly during a war, is no easy feat. The mods often have to de-escalate conversations and step in to “reset the room” after a heated conversation ignites. Majed says the goal of the room “is not to create a completely safe space, or tone police anyone, but to create a space that ordinary Israelis and Palestinians can simply “tolerate.”

In start-up parlance, it’s a “Minimum Viable Product” for Israeli-Palestinian dialogue.

And based on the conversations I eavesdropped on, it worked.

The room was a non-stop, flowing conversation of personal stories about their relationship to the land. Despite the size of the room, it felt intimate and family-like. There were recurring arguments about the meaning of words like “colonialism,” “Zionism” and “occupation.” I even heard the occasional “I love you.”

Before this room, I’d heard Israelis and Palestinian say many things to each other, but never that.

Meaningful listening is something that Israeli and Palestinian leaders have not done in more than two decades. There has not been an official dialogue between Israeli and Palestinian leadership since the Camp David peace talks ended in the year 2000.

Not surprisingly, the communication breakdown has correlated with a drastic increase in bloodshed.

An estimated 4,000 Israelis and Palestinians were killed in the 2nd Intifada from 2000-2005. The 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah, killed more than a thousand Lebanese and Israeli civilians. The 2008-2009 Gaza war between Israel and Hamas, killed at least 1166 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. The next Gaza war, in 2014, killed at least 2125 Palestinians and 73 Israelis. This latest round of violence in Israel and Gaza killed 248 Palestinians and 12 Israelis. Between each one of these gruesome wars, thousands of people were killed or wounded in violent flare-ups that don’t get classified as “wars.”

Each cycle of violence follows the same patterns. Rockets, bombs. Rockets, bombs. Rockets, bombs. Eventually, a ceasefire or tahdia, a lull as it’s called in Arabic, is declared. Social media quiets down. The international media goes home. Both sides go back to their respective echo chambers, blame the other side for starting the violence, and then claim to be the “winners.”

What they won exactly is not clear.

In reality, with each round of violence, both sides only lose. Israel does not win lasting peace or security. Palestinians do not win land or freedom. On the contrary, war begets war. Militants become more militant and more popular. With each round of violence, a brand new generation of children is traumatized, adding to the generational trauma they inherited from their parents and grandparents. In the Israeli town of Sderot near the Gaza border, a study showed more than 75% of children exhibited symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In Gaza, 91% of children have PTSD.

Economic and military power have disincentivized Israeli leadership from focusing on the conflict, despite the clear moral and strategic reasons for doing so. Israel’s new, broad government is unlikely to change anything vis-a-vis the Palestinians because it will fragment the shaky coalition. The Palestinians, meanwhile, are physically and politically divided between Hamas rule over Gaza (blockaded by Israel and Egypt) and Fatah rule over the occupied West Bank. They haven’t had a democratic election since 2006.

How can ordinary Israelis and Palestinians try to break the cycle of violence when their leaders seem perfectly ready to drag on the conflict for another 73 years?

There’s only one way. They need first to hear, and then listen to, each other’s stories.

As an international journalist, I had two privileges Israelis and Palestinians did not have.

The first was that I could travel back and forth freely all over “the Land”. (For simplicity and inclusivity, this is how I’ll label what some call “Israel” and others call “Palestine”. Everything here, you see, has two names.

I remember spending so many days walking in the Judean Mountains as they’re known in Hebrew, or Hebron Mountains, as they’re known in Arabic. They are mostly gently verdant rolling hills with large patches of brownish-orange dirt. In the spring, bright red anemone wildflowers called “calaneet” in Hebrew or “Shaqa'iq An-Nu'man” in Arabic sprout up among the olive groves. The brisk, sweet air invites you to find your path and stroll. Wherever I ended up, I was offered a strong black Turkish coffee or sugary nana (mint) tea from tiny plastic cups. (Hospitality was never up for debate)

Walk here and you’ll discover an enchanted, sublime landscape that has long been a canvas for human imagination and storytelling. The Old Testament refers to it countless times as “the land flowing with milk and honey.” This is the earliest known description of the Land that became “holy” to so many. These hills are the setting of humanity’s most popular stories, recounted in the Torah, New Testament, and Quran. In the Land, these myths are the tapestry on which these two cultures weave their modern narratives.

I often went from Israeli settlements on the top of the hill to Palestinian villages in the wadi, or valley, below, in search of these modern stories. I could hike from village to village, since they were often within spitting distance of each other. The gap between the narratives, however, was worlds apart.

On the hill, I heard that the Jews were the original rulers of the Land. In the wadi, I heard that the Jews took the Land from the Palestinians.

On the hill, I heard that the holy site in Jerusalem is called the Temple Mount. In the wadi, I heard that the holy site in Jerusalem is called Al Aqsa.

On the hill, I heard that Zionism gave Jews back their homeland. In the wadi, I heard that Zionism exiled the Palestinians from theirs.

On the hill, I heard that today is Independence Day. In the wadi, I heard that today marks the “Nakba” the Catastrophe.

On the hill, I was in Judea and Samaria, Israel. In the wadi, I was in the Occupied West Bank, Palestine.

On the hill, slicing through the land was the “Security Fence.” In the wadi, slicing through the land was the “Apartheid Separation Wall.”

On the hill, Hamas started the war by firing the first rocket. In the wadi, Israel started the war by kicking out another Palestinian from their house.

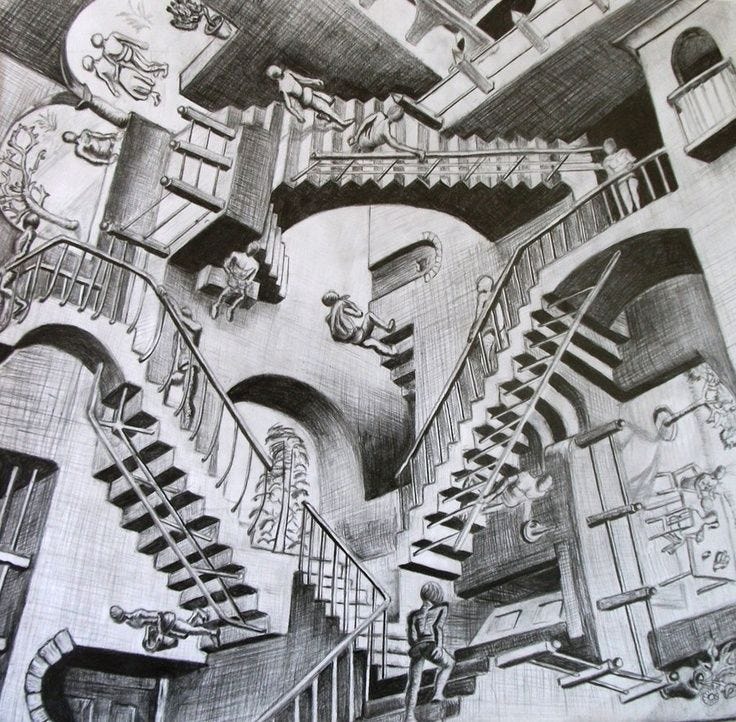

Over a decade, I shot thousands of hours of video interviews in the Land. Sometimes I tried to challenge each side with the narrative of the other side, but ultimately it didn’t register. They could hear the words of the other side but seemed deaf to the possibility of truth or sentiment behind them. Like the M.C. Escher lithograph “Relativity” featuring two parallel staircases that never meet and appear to be governed by two different gravity sources, it felt like Israelis and Palestinians are doomed to share the same house, but never intersect. They walk and talk over and under each other, and as a result, live in a perpetual state of misunderstanding.

Ultimately, it was my job to listen, not to get Israelis and Palestinians to listen to each other. I begrudgingly became the messenger of the West, bringing to the comfort of their living rooms two wholly incompatible narratives, often weaving them together in post-production. When I was accused of bias by hard-liners from each tribe, I knew that I had achieved balance.

After ten years, I felt like I was spinning my wheels. Hopeless, tired of the cycles of violence, and probably a bit traumatized by it myself, I exercised my 2nd privilege as an international journalist. I left the region in 2012.

I started a technology company in the United States, called Storyhunter, to help freelance filmmakers and journalists connect with global publishers and tried to put the conflict behind me. Even though I was thousands of miles away now from the region, my subconscious mind still felt like a hostage to the conflict. I devour any news about it, usually with a sense of dread. When will the next round of violence begin? It happened in 2012. And then again in 2014. In early May 2021, it happened again. A new war, the same pattern. I can’t help but get sucked right back in.

When violence erupts in the Land, the narrative on the news media, with few exceptions, is an oversimplified melodrama with caricatures of good and evil, right and wrong, oppressed and oppressor, depending on the media outlet and what side they perceive their audience to be on. The media typically reinforces the polarization of the two warring tribes, Israelis vs. Palestinians as if they are fighters in a Las Vegas title fight. It pits them against one another and then profits generously from the melee.

Social media is infinitely worse. On FB, IG, and Twitter, I don’t hear about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for 7 years, and then as soon as the rockets fly, I’m getting blasted by my “pro-Israel” friends (most of whom have never lived in Israel) whose basic message is to “Defend Israel from Jihadi terrorists who shoot rockets for no reason” and by my “Pro-Palestinian” friends (most of whom have never lived in Palestine) whose basic message is to “Defend Palestine from IDF soldiers who kill innocent Palestinian children for no reason.”

During the escalations, social media becomes a virtual minefield of one-sided histories, false narratives, and misinformation.

There is this knee-jerk, fear-based reaction for each side to get entrenched back in their camp. They get defensive. They stop listening and start accusing. They seem to say: “I am a proud X. Here’s our history of the X people. We are clearly on the side of righteousness and good. I don’t need to hear your story.”

These were exactly the same messages I got three wars ago.

The difference in the latest war was that now the messages come from influential celebrities and pundits who have not done their homework. The propaganda is more visual, more manipulative, and more scalable -- going to a less informed audience. Because of social media algorithms that lead its victims, aka “users,” into rabbit holes of biased and false information, with your side pre-selected for you.

I was ready to write off all social media entirely until my wife invited me to this Clubhouse room entitled Balance: Meet Israelis and Palestinians. At first, I was skeptical. I had used the Clubhouse app before, but never really saw it as anything more than another corporate marketing tool. But once inside, I found something quite different from anything else I’ve seen on social media, or in the real world:

An actual dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians.

The main rule of the Clubhouse room is that each side, according to ethnicity, would take turns. Moderators made sure that after an Israeli or Jewish voice speaks, a Palestinian or Muslim voice speaks next. Men and women get equal time on the mic. They drew a diverse group of people onto the “stage.” In a given hour on this chat, you might hear from a twenty-something Palestinian man from the Dheisheh refugee camp in Bethlehem who wants a 2 state solution, a hardline Israeli woman who works as a translator from Rishon Letzion, a Hamas sympathizer in the U.S., a queer, formerly ultra-orthodox Jew from NYC, an IDF commando turned activist supporting a 1 state solution, a human rights worker and Yogi from Gaza, or an Iranian Muslim who had never left Iran. This is just one hour. Sometimes it felt like a whirlwind of disparate stories. Other times, it felt like the most gripping, voyeuristic window into human trauma imaginable. In these moments, not a single soul left the room.

For many, just coming to the room was difficult, and potentially dangerous. A Gazan man came on stage with a trembling voice, “How can I meet with you if you refuse to give us any justice and human rights?”

Guy, a silky-voiced, 13th-generation Israeli film director turned sourdough bread maker turned Clubhouse moderator, sensed that this man needed some reassurance, “My brother, I am a 47-year-old Israeli. We have never met before and I suspect that is by design. I don’t expect your trust right now. But I would like to earn it.”

On occasion, the room feels like a group therapy session.

In the middle of the night (Holy Land Time), an Israeli woman told the group about her post-traumatic stress from losing a loved one to a suicide bomber during the 2nd Intifadah. Two decades later, she panics every time she sees a public bus.

The following morning, a Palestinian woman spoke about the humiliation she felt once at a checkpoint. IDF soldiers forced her to strip naked along with a group of other women. After the exhaustive strip search, she couldn’t find her shoes. She eventually discovered a pile of Palestinian shoes - and dug through them to find her pair.

Palestinians heard Jews talk about the horrors of the Holocaust, with no detail spared about the death marches and gas chambers designed to annihilate a people.

Israelis heard Palestinians talk about the horrors of the Nakba, including the murders of innocent civilians and the rape of Palestinian women, designed to banish a people from the Land.

Palestinians learned that not all Jews want or support the occupation.

Israelis learned that not all Palestinians support Hamas or a 1-state solution.

Moderators tried to steer the conversation away from what they call “the oppression Olympics” where each side tries to compete for how much historical injustice they’ve faced. They’re all medalists.

Loaded, trigger words like “Terrorist” or “Apartheid” were often sidestepped to keep people in the room. Instead of trying to fit labels on these concepts or debate terminology, the mods re-directed people to share their personal narratives instead.

“We’ve debated these words a thousand times, and where have they gotten us? The goal of the group is not to win points, but for us all to share our traumas. Through that shared pain, we will come closer together,” says Guy.

A sniffling former IDF soldier came into the room one night and told his story. “I stood in the homes of Palestinians while my fellow soldiers searched a house. I made sure not to point my M-16 at the children. I taught them how to count in English to try and distract them from what was happening. But I know all they saw was my M-16.” Between sobs, he muttered, “No one should have to live in fear like that. I want you to know that I’m sorry.”

Suddenly a female voice came out and said, “I was that little girl.”

She went on to recount the sensation of standing in her living room in the middle of the night in Ramallah as a small child, petrified and confused, as she stared at the barrel of an M-16 belonging to an Israeli soldier. Eventually, she said to the ex-soldier, “Thank you for being vulnerable. I can hear the pain in your voice. I am 31 now and I still feel my pain.”

My wife and I huddled over the single phone that still had battery life, a world away in Miami Beach, both of us with gooseflesh, totally gripped.

The next night, the Israeli soldier came back into the room, still sounding weepy, and asked in earnest to any Palestinian in the audience, “If we accept your narrative and provide you freedom, are you saying the violence will stop? Are there enough Palestinians who will say chalas (stop it) ?”

The same little girl from Ramallah, now a woman, exclaimed “Yes! We will stop all violence the day you provide us with dignity and human rights. Your transformation gives me hope that it can happen.”

Majed, who goes by “Maj” is a self-identified Palestinian-Israeli, 33, who started the group along with his friend Moshe Markovich, 32, a self-identified Jewish American. The two met 12 years prior in a Jerusalem gym, while Moshe was living in Israel attending Yeshivah. They were each going through their own separate personal dramas at the time and found in each other someone they could talk to without any judgment. They ate together, traveled together, and brought each other into their respective worlds. Majed would take Moshe to Bethlehem and Ramallah, and Moshe invited Majed to meet some of his fellow Yeshiva bochurs.

“My friends could not believe I had a Palestinian best friend,” said Moshe.

Majed and Moshe started chatting on Clubhouse a few months before the war with a small group of 5 friends. It expanded. Majed received death threats and left Clubhouse for two months.

He told me in an interview, “The more these anti-dialogue people came at me the more I realized this room needed to happen. As a gay Palestinian man, people have always tried to silence me for my identity. This has made me even more audacious to tell my story.”

Many of the Palestinian mods have received death threats from hardliners who are against dialogue with Jews or Israelis since they believe it “normalizes oppression.” Some of the Jewish mods have been called “self-hating Jews” or “Israel bashers” because they are willing to talk with Palestinians or criticize Israeli policies. There are online trolls gaining access to the room with fake accounts who then try to block the dialogue. Hamza Khan, a so-called “3rd party neutral mod” from Maryland who has never been to the Land, received a death threat. He wasn’t fazed. “This guy threatened me. I invited him over to my house for a kebab.”

Majed has received the majority of the death threats, some via Instagram direct messages. He was asked to join other rooms in Clubhouse in which he was “cornered by other activists” who accused him of having a “colonized mind” and then threatened him for “speaking with the enemy.”

As Maj explains “ Dialogue is sometimes the most radical thing you can do. I reject the idea that we can't talk until there's justice and peace.”

On Day 3 of the war, Majed and Moshe decided to open a private chat with about 60 people. They called the new room Balance: Meet Palestinians and Israelis. More people wanted in. On Day 4 they opened it up to the public. They soon found themselves in a room with more than 1,000 people.

The mods learned on the fly how to channel the extremist voices into the conversation, rather than force them out. They brought on dozens of mods with some more training in conflict resolution, psychology, politics, and religion.

Guy, now living in LA, stumbled upon the room, even though he was initially skeptical of both Clubhouse and the group itself. He told me in an interview, “Hearing Maj’s voice and story pierced my heart.”

He stuck around and became a mod, prioritizing this Clubhouse room over basic human needs. “I was in and out of sleep for 14.5 days, listening for my name so I knew it was my turn to speak.”

He was instrumental in helping Israelis feel safe enough to join the conversation

A self-described “right-wing” 55-year-old Israeli woman from Rishon Letzion came into the room on May 17th. According to Guy “She came in hot and articulately defended the most extreme Israeli position in an aggressive way. I was afraid she would turn people away from the room,” Guy said. She got out what she needed to say, and eventually stayed and listened to Palestinian stories. A couple of days later, her opinions of the Palestinians changed. “My views changed more in 48 hours than in 55 years,” she said “All my life I’ve been right wing, but through what I heard here, I discovered my left wing, and understood that my whole life I've been flying in circles.“

She is now a mod of the group, recruiting Israeli friends to join.

“Witnessing these genuine transformations happen showed me that we are onto something. For the first time since the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, I have some hope,” Guy told me.

One night, a Palestinian doctor from a village outside Hebron told his personal story about the occupation and at the end of his 8-minute monologue said, “I want to tell all my Jewish brothers and sisters that suicide bombers do not represent me, the Palestinian people, or Islam.” A Jewish American halfway across the world in Los Angeles listened to the whole story and told me in a private Clubhouse chat, “I spent more than 50 hours in the room and this is the thing that sticks out to me. I’ve never heard a Palestinian say those words.” They connected through DM and now Facetime regularly. “I now have my first Palestinian friend, “ he told me.

Clubhouse was founded in 2020 by Paul Davison and Rohan Seth who told me via email they created it “with the goal of helping people connect.” It is designed for longer form, audio storytelling, and deep listening. According to Clubhouse CEO Paul Davison, “We have been astonished and humbled by this room.”

Like all social media apps, Clubhouse has been used for spreading vile messages and fake news too. But what is unique is its ability to be used for exactly the opposite of that. As Paul puts it, “Through the power of direct person-to-person conversation, hundreds of thousands of people have found common ground. Clubhouse’s focus on the listening part is what differentiates it from its social media competitors.

As Guy puts it, “Clubhouse made us listen for hours before anyone gives you a chance to talk back - and in those hours, something magical can happen.”

Could listening and personal storytelling be the “killer features” for sectarian conflict resolution?

Two 20th-century examples suggest that may be the case.

The first one is South Africa, the country my great grandparents presciently fled to from Lithuania before WWII. As a 5-year-old boy visiting my grandparents in Cape Town in the mid-1980s’, I remember learning how to read through the racist signs of apartheid. “Whites only Beach,” “Black, Colored, and Asian Toilet.” My parents didn’t believe those absurd signs would come down in their lifetime.

But, in 1995, they did, largely because of the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Listening to this Clubhouse group transported me back to this era when I remember hearing some of the darkest, most painful personal stories of South Africans during Apartheid.

The TRC was arguably the most important component of the political agreement between Nelson Mandela, leader of the African National Congress (ANC), and the leader of the ruling white Nationalist party, FW DeKlerk. Mandela understood the deep trauma of his people and the complex feelings of his white counterparts. He knew that, after four decades of trauma and fear of the other side, true reconciliation was not going to happen by just signing some paperwork. Trust would take time to build. But how to start the process?

The brilliance of the South African TRC was its focus on the personal narrative of the victims, not on politics or jargon. This made every testimony relatable. I remember hearing heinous testimonies of torture, killings, and abductions, at the hands not only of the White nationalist apartheid regime, but also by members and leaders of the African liberation movements themselves.

The second key feature of the commission was its transparency. These stories were told in public hearings. You could hear the accents, pitch, and tone of each voice. The audience of the stories was not the court, but rather the entire country. It was a national airing out of dirty laundry.

In total, 22,000 victims told their most horrendous, personal stories publicly.

The TRC gave the victims a powerful public platform. They felt “heard”. Their trauma was acknowledged. Once the victims told the stories — only then — could they forgive the perpetrators. These stories were patched into the collective patchwork of South African history, allowing the two sides to move on and write the next chapters together. The TRC, under the leadership of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, granted 1,500 amnesties for thousands of crimes committed during the apartheid years. Most importantly, it provided the emotional cement necessary for the political agreement to stick. As Nelson Mandela put it, “In the end, reconciliation is a spiritual process, which requires more than just a legal framework. It has to happen in the hearts and minds of people.”

The “miracle” Clubhouse room, on many nights, felt like a virtual truth and reconciliation commission with Middle Eastern accents. As in South Africa, there is no shortage of Israeli and Palestinian victims. As Maj expressed one night after a traumatic story was revealed, “Your pain is someone else’s shame. Just by saying this story, both sides can now heal.”

Unlike South Africa, it appears that Israeli and Palestinian leadership do not currently have the will or power to settle this conflict politically. The founders and moderators of this Clubhouse group do not care. “We are bypassing our leaders and the fences and the rockets and the bombs to meet. We are trying to hack that system,” said Guy. They are trying to amass a groundswell of understanding that may one day turn into a tsunami, forcing their leaders to reach a political agreement.

In this sense, the model is closer to the second sectarian conflict that ended in the late 90s. This was the bitter, sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles. Many years before the Good Friday agreement was signed in 1998, peace activists laid the groundwork for negotiation by fostering dialogue between the combatants themselves.

Reverend Dr. Gary Mason, a self-described “bigot”, spent 28 years as a clergyperson in Belfast, which allowed him to listen to people. Hearing their stories transformed him. He then built a grassroots movement over decades to try and transform others through physical meetups along with personal storytelling.

“To be without memory would be to be without a life and a world,” he wrote.

After almost 35 years of fighting in a bitter sectarian conflict that killed thousands of people, mostly civilians, two of the loyalist paramilitaries groups - the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Red Hand Commando - turned over their weapons statement in Gary’s church.

The Irish model is proof that solving long-running, deadly tribal conflicts can happen through a bottoms-up approach with dialogue as a key tenet. It also shows that it doesn’t happen overnight.

As Dr. Gary Mason, puts it, “If you want peace now, you need to start working on it 20 years ago.

The hard work he’s referring to, when it comes to resolving bitter conflicts, is moving more people toward empathy, rather than extremism. Memories don’t go away, but the pain associated with trauma can actually be shed. This ain’t easy. As trauma compiles on top of trauma, hardline attitudes eventually become the norm. The other tribe gets vilified so much in their stories that they are often unwilling to engage in dialogue with them. By refusing to “normalize” the so-called “enemy” in conversation, they remain ignorant of their narrative.

Empaths, on the other hand, are willing to listen to and empathize with their so-called "enemy”. They are capable of listening to the stories of the other side and feeling the pain of others. For hardliners, there is only one history that matters. For empaths, there can be multiple histories.

A new genetic study on empathy, the largest one ever done, with 46,000 participants, led by a team of scientists at the University of Cambridge team, working with the genetics company 23andMe, found that genetics was not the dominant factor in determining empathy. We already knew from prior research that on average, women are slightly more empathetic than men. What we learned in this new study is that women are not born that way. They develop it throughout their lives, through socialization or their gender-specific experiences.

This is good news for peace workers. It means that one can develop more, or less empathy, as a result of one’s experiences. Hardliners can become empaths, and vice versa. In this regard, we are more fluid than we think.

Back in the Land, there are hundreds of groups on the ground working tirelessly towards peace for many years with very limited success. They face many physical, political, and cultural obstacles. While this Clubhouse group is not immune to some of these challenges, its accessibility makes it novel. In a land that is divided, where checkpoints and fear prevent physical meetings, this app is transcendent. With a click of a button, you can hear the personal stories of a person you may have been taught to hate or fear.

The magic of listening to the narrative of the other is that sometimes, just that very act, can transform your opinions about the other side. It reveals blind spots in your narrative. It teaches you about your indoctrination. Learning multiple histories gives the listener the gift of awareness of their specific cultural orientation. History is a bit like a puzzle, it’s an amalgamation of many stories about reality that sometimes fit together and sometimes do not. Gathering more puzzle pieces gives one a better ability to approximate the truth.

The Jewish and Palestinian narratives happen to fit quite nicely with one another because as it turns out, we were one people living on the Land longer than they were two separate nations fighting over it. Jews and Palestinians share the same genetic roots. The Land feels familiar to both peoples because it is in our bones and blood. At a certain point, the cultural narratives, religious affinities, and footsteps simply diverged. The Land, this shared canvas and memory, was abruptly fractured.

Could it be that the stories I learned on the hill and in the wadi are both true?

Yes.

Could it be a “Security Fence” AND a “Separation Wall?” The Temple Mount AND the Al Aqsa Mosque? A shared homeland for Jews AND Palestinians?

Yes, yes, and yes!

Listening to the other side’s narrative allows one to see the perspective and truth of an “enemy” you thought you knew. It forges a genuine understanding you cannot glean from any other form of learning. It softens hardliners and turns them into empaths with remarkable efficiency. Clubhouse’s software, combined with a special community of moderators, offers a platform for building empathy, and potentially, for scaling it.

Perhaps if this room can get enough personal stories shared, as in South Africa, it can heal the hearts of enough Israelis and Palestinians to focus on the future, rather than fight about the past.

Perhaps if this small Clubhouse room can grow big enough, empathy will replace extremism in the hearts of so many that their leaders will be able to settle this conflict, as it did in Northern Ireland.

Perhaps we can then build a model to solve all other sectarian conflicts around the world.

I recognize this may all seem like pie in the sky. But the alternative for Israelis and Palestinians is a never-ending story of war. Why not try something new?

The Clubhouse group is not naive. They know they face an uphill battle. They witnessed how effective the room was, but the question remains how will this huge population of hardliners change if they are unwilling to even enter it? As Guy says, the “real challenge is reaching people before they reach this space.”

After more than two weeks of continuous dialogue the “miracle room” winded itself down. The team is planning on figuring out how to get more people to a new room and is organizing themselves to see how they can take this project to the next level.

They are now meeting once a week for only 12 hours, but the plan is to reach many more Israelis and Palestinians, with spinoff groups embracing the methodology that worked in the Balance room.

Majed’s hope is for “many millions of Israelis and Palestinians to go through this sacred space.”

This may not be so crazy considering the scale of social media today. If Clubhouse can grow as a platform and become a new model for a healthier type of social media consumption, then this pipe dream may just come true. (Facebook, Twitter, and Spotify have all launched Clubhouse copycats of their own).

In the meantime, my challenge to all my Israeli and Palestinian friends is this: If you care to break the cycle of violence, if you love the Land and wish for peace for your children, do the most radical thing imaginable. Meet halfway between the hill and the wadi, or in a virtual room on Clubhouse, and just listen.