Pakistan

We entered Pakistan through Lahore, her cultural capital. Lahore is a stinky city, but is still a charming place. We stayed at a hostel there called the Regale Internet Inn for 3 dollars a night. It was a nice hostel, with free internet, a kitchen to make your own eggs, and a proprietor who offers guests the opportunity to see a truly amazing spectacle. Thursdays in Lahore are very special. They have Qawwali at the central shrine. Qawwali groups are Muslim musical collectives that feature various instruments and a few singers that cry out poetic Koranic verses. They come from all over the country and are showered with Pakistani rupees upon audience approval. We were treated to front row seats for this event. I was glad for this opportunity, because up until the Qawwali, I was twiddling my thumbs at an England-Pakistan cricket test match. Cricket is the one sport I can’t bear to watch live, partly because the test matches take place over a period of a few days, which diminishes the relevance of any one moment in a match, but mostly because I find it to be a boring testosterone-less game that is too proper, too sterile, and too colonial for my liking. Here's my theory as to why cricket was the key to the success of the British Empire: First they came and stole all a nation’s wealth and just when you thought it couldn't get any worse for the natives, they forced the poor people to put on white, tight clothes and play a game that would bore them into a state of complete and utter complacency. (To my late grandfather Harold, who loved the game of cricket like another grandson, I’m sorry but we don’t see eye to eye on this one.)

The Pakistanis unfortunately really like cricket. This is an impromptu game near Muzzafarbad in Kashmir.

After the cricket and Qawwali, I was wiped out and probably should have stayed home for the main event. But I couldn’t resist what was billed as an evening of Sufi invocations to Allah, featuring a deaf and dumb drumming prodigy, worshippers enraptured in a spiritual trance dance, and enough hashish to kill a Rastafarian.

After a rather scary rickshaw ride I was in an outdoor patio area and filled with hundreds of Muslim men, presumably Sufis, practitioners of a mystical form of Islam. The only women were of the Western breed. Charas and a mysterious non-alchoholic beverage was perpetually being passed around and swallowed up by the seated crowd, a mass of cross-legged bodies eagerly anticipating the onset of the show. Finally, the two drummers began. It began as a slow beat, then escalated to an orgasmic crescendo, and then slowed down just as it became too intense, without a single pause in the music for four hours. Occasionally a person would erupt with Islamic fervor, screaming out to Allah at the top of their lungs. The deaf drummer was simply brilliant, so attuned to the vibrations of his percussion that his musical energy seemed to be dispersed equally amongst all our bodies. The four hours went by like the blink of an eye and afterwards everyone was completely drained. They passed around a hot and fresh flatbread with a delicious curry flavored spread and everyone indulged. Some more than others. After about 5 pieces, I was already feeling rumbles in the Bronx, and when I woke up the next morning I knew that there was something seriously wrong with my stomach.

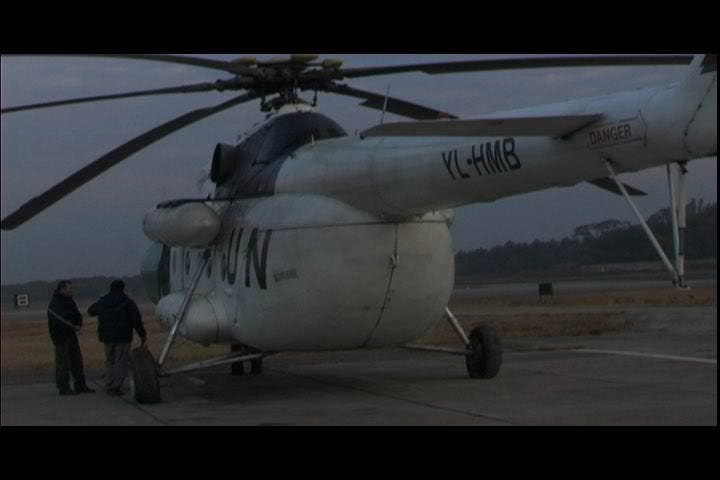

That day we headed to Islamabad, a city that I will have to revisit someday because I spent the better part of 48 hours alternating between shivering and sweating on a (thank the lord) Western toilet in a two star hotel room. We had made arrangements to fly up to the earthquake devastated regions in a UN chopper the next day, so I knew I had to get better quickly. I walked briskly and nervously to the pharmacy, praying that I would just be able to tell them what was wrong with me without having to provide a demo. I made it there and back safely with my new hero, Cipro the wonder drug. This stuff is amazing. I felt stable enough to fly the next morning and was on my first-ever helicopter ride to Pakistani controlled Kashmir, to a city called Muzzafarbad.

The pic is out of focus but you can kind of make out the destruction.

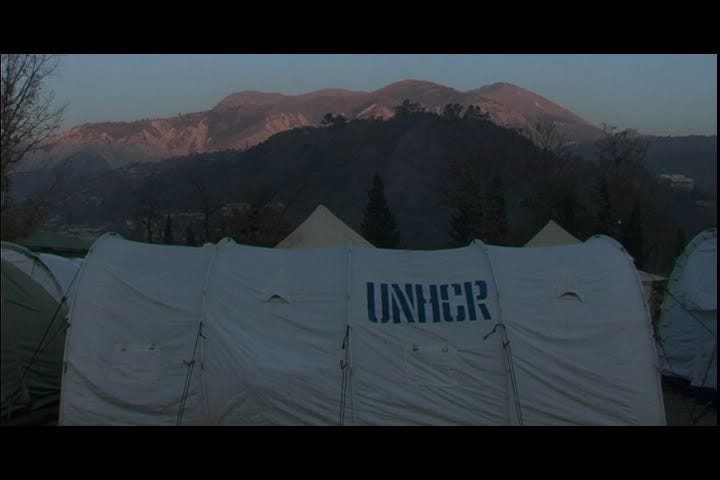

One of the thousands of "affectee camps" scattered throughout Northern Pakistan. There are an estimated 3 million people still homeless.

Flying over the city, the queasiness I felt in stomach turned into a more serious sensation that went up and grabbed me by the heart. It was a combination of shock and dread that instantly made my little diarrhea problem an afterthought. I was in Thailand four months after the tsunami and I’ve never seen such widespread devastation like I saw in Pakistan. They estimate that 80 percent of the buildings of the city of Muzzafarbad were leveled, and this fact sprang to life with our bird’s eye view. I almost didn’t want the chopper to land, fearful of what I might see there. When it did land I still could not believe the sights I would see and the stories I would hear. A part of me still wishes that chopper never landed.

Most of these stories and faces I don’t even want to revisit in my mind. The most painful ones I have probably repressed. Now, two weeks later, the memories pop into my consciousness like flashes of light, a mass grave of 41 children, a woman missing her nose, an orphaned child walking through rubble with no shoes. I don’t like to think about these things so I don’t, and then my consciousness fades to black and I try to think about the good things I saw there, the memories that I hold on to not just because they comfort me, but because hopefully they’ve changed me in some way that I will never be able to qualify, but deep down I know its good change. At a certain point I began asking myself what it is about these tragic sites that attracts me. It’s certainly not the grisly tales of death and destruction. It’s not the suffering and pain of the survivors. But rather it’s the rebirth and hope that miraculously and inevitably springs to life in places like Koh Phi Phi, Thailand, and Balakot, Pakistan. It shakes my philosophies to the core. How can human nature be essentially evil if there is absolutely no good reason for all these people to help one another, yet they still do? On the flipside, there is also usually no good reason for nations to go to war, yet they still do. Bizarre creatures we humans are. It gives me hope to see Africans, Americans, Europeans, Asians, Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, and Jews all working together for a common cause, a common goal of helping a village that none of these people even knew existed before it was destroyed. Ironically, it is only in a major disaster relief operation that I have seen this “global community” with my own eyes.

What I hope to take with me from Pakistan is the resilience and hospitality of these tough mountain people. I hope not to forget the old man with the silver beard who had lost his family and home in the earthquake, and still invited us into his cold, dreary tent for a hot lunch and a cup of chai. I hope not to forget the little girl with a severed arm who kept looking at her stub as if she still wasn’t used to it, but still managed to laugh when I made a funny face. I hope not to forget the teacher who lost 150 students when the schoolhouse collapsed and is now teaching again in a tent. And I certainly won’t forget the thousands of people who are freezing and perishing right now due to inadequate shelter. It's so frustrating that I am powerless to prevent it.

The old people are the worst off. Kids are usually too young to comprehend the tragedy and are more adaptable.

This boy is paralyzed.

This girl lost all her siblings and still manages to smile.

The main problem facing the Pakistanis in the earthquake-affected regions this winter: Lack of Shelter. The elements of wind and snow and cold will combine to kill many people that normally have the tools to brave the harsh winter. Hypothermia and respiratory infections deaths will increase because they are now exposed to these elements. Relief agencies are doing all they can to help. The money is there, the distribution systems are in place. The problem is a global shortage of winterized tents to replace these homes, and many of these people will. The alternative is corrugated iron, which can be used to build temporary structures to keep out the elements. If you or anyone you know is in the tent business or sheet iron business and can sell or donate products to the relief effort, please contact this person:

Her name is LAILA KHAN and she is with the International Rescue Committee:

laila@irc-pk.org

Unloading food donated by various countries (including US) through the World Food Program.

Fidel Castro sent an enormous delegation of Cuban doctors to help out.

We were lucky: The UN provided us with a winterized tent.

Rushing the corrugated iron to the mountains.

Men going through the rubble in search of corrugated iron.